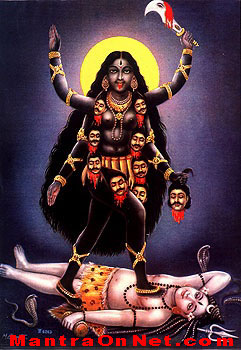

The goddess Kali is almost always described as having a terrible, frightening appearance. She is always black or dark, is usually naked, and has long, disheveled hair. She is adorned with severed arms as a girdle, freshly cut heads as a necklace, children's corpses as earrings, and serpents as bracelets. She has long, sharp fangs, is often depicted as having claw-like hands with long nails, and is often said to have blood smeared on her lips. Her favorite haunts heighten her fearsome nature. She is usually shown on the battlefield, where she is a furious combatant who gets drunk on the hot blood of her victims, or in a cremation ground, where she sits on a corpse surrounded by jackals and goblins.

Many texts and contexts treat Kali as an independent deity, unassociated with any male deity. When she is associated with a god, however, it is almost always Lord Shiva. As his consort,wife, or associate. Kali often plays the role of inciting him to wild behavior. Kali's association with Lord Shiva, unlike Parvatl's, seems aimed at exciting him to take part in dangerous, destructive behavior that threatens the stability of the cosmos. Kali is particularly popular in Bengal, although she is known and worshiped throughout India. In Bengal she is worshiped on Dipavali. In this festival, and throughout the year at many of her permanent temples, she receives blood offerings. She is also the recipient of ardent devotion from countless devotees, who approach her as their mother.

Early History

The earliest references to Kali in the Hindu tradition date to the early medieval period (around A.D. 600) and usually locate Kali either on the battlefield or in situations on the periphery of Hindu society. In the Agni- and Gamda-puranas she is mentioned in invocations that aim at success in war in against one's enemies. She is described as having an awful appearance: she is gaunt, has fangs, laughs loudly, dances madly, wears a garland of corpses, sits on the back of a ghost, and lives in the cremation ground. She is asked to crush, trample, break, and burn the enemy. In the Bhagavata-purana Kali is the patron deity of a band of thieves whose leader seeks to achieve Kali's blessing in order to have a son. The thief kidnaps a saintly Brahman youth with the intention of offering him as a blood sacrifice to Kali.

The effulgence of the virtuous youth, however, burns Kali herself when he is brought near her image. Emerging from her image, infuriated, she kills the leader and his entire band. She is described as having a dreadful face and large teeth and as laughing loudly. She and her host of demons then decapitate the corpses of the thieves, drink their blood until drunk, and throw their heads about in sport.

Banabhatta's seventh-century drama Kadambari features a goddess named Candi, an epithet used for both Durga and Kali, who is worshiped by the Sabaras, a tribe of primitive hunters. The worship takes place deep in the forest, and blood offerings are made to the goddess Vakpati's Gaudavaho (late seventh or early eighth century) portrays Kali as an aspect of Vindhyavasim (an epithet of Durga). She is worshiped by Sabaras, is clothed in leaves, and receives human sacrifices In Bhavabhuti's Malatimadhava, a drama of the early eighth century, a female devotee of Camunda, a goddess who is very often identified with Kali, captures the heroine, Malati, with the intention of sacrificing her to the goddess. Camunda's temple is near a cremation ground. A hymn to the goddess describes her as dancing wildly and making the world shake. She has a gaping mouth, wears garland of skulls, is covered with snakes, showers flames from her eyes that destroy the world, and is surrounded by goblins.

Somadeva's Yasatilaka (eleventh to twelfth century) contains a long description of a godess called Candaman. In all respects she is like Kali, and we may understand the scenario Somadeva describes as suggestive of Kali's appearance and worship at that time. The goddess adorns herself with pieces of human corpses, uses oozings from corpses for cosmetics, bathes in rivers of wine or blood, sports in cremation grounds, and uses human skulls as drinking vessels. Bizarre and fanatical devotees gather at her temple and undertake forms of ascetic self torture. They burn incense on their heads, drink their own blood, and offer their own flesh into the sacrificial fire.

Kali's association with the periphery of Hindu society (she is worshiped by tribal or low-caste people in uncivilized or wild places) is also seen in an architectural work of the sixth to eighth centuries, the Manasara-silpa-sastra. There it is said that Kali's temples should be built far from villages and towns, near the cremation grounds and the dwellings of Candalas (very low-caste people)

Kali's most famous appearances in battle contexts are found in the Devl-mahatmya, In the third episode, which features Durga's defeat of Sumbha and Nisumbha and their allies. Kali appears twice. Early in the battle the demons Canda and Munda approach Durga with readied weapons. Seeing them prepared to attack her, Durga becomes angry, her face becoming dark as ink. Suddenly the goddess Kali springs from her forehead. She is black, wears a garland of human heads and a tiger skin, and wields a skull-topped staff. She is gaunt, with sunken eyes, gaping mouth, and lolling tongue. She roars loudly and leaps into the battle, where she tears demons apart with her hands and crushes them in her jaws.

She grasps the two demon generals and in one furious blow decapitates them both with her sword. Later in the battle Kali is summoned by Durga to help defeat the demon Raktabija. This demon has the ability to reproduce himself instantly whenever a drop of his blood falls to the ground. Having wounded Raktabija with a variety of weapons, Durga and her assistants, a fierce band of goddesses called the Matrkas find they have worsened their situation. As Raktabija bleeds more and more profusely from his wounds, the battlefield increasingly becomes filled with Raktabija duplicates. Kali defeats the demon by sucking the blood from his body and throwing the countless duplicate Raktabijas into her gaping mouth.

In these two episodes Kali appears to represent Durga's personified wrath, her embodied fury. Kali plays a similar role in her association with Parvati. In general, Parvati is a benign goddess, but from time to time she exhibits fierce aspects. When this occurs. Kali is sometimes described as being brought into being. In the Linga-purana Lord Shiva asks Parvati to destroy the demon Daruka, who has been given the boon that he can only be killed by a female. Parvati then enters Lord Shiva's body and transforms herself from the poison that is stored in Lord Shiva's throat. She reappears as Kali, ferocious in appearance, and with the help of flesh eating pisacas (spirits) attacks and defeats Daruka and his hosts.

Kali, however, becomes so intoxicated by the blood lust of battle that she threatens to destroy the entire world in her fury. The world is saved when Lord Shiva intervenes and calms her. Kali appears in a similar context elsewhere in the same text. When Lord Shiva sets out to defeat the demons of the three cities. Kali is part of his entourage. She whirls a trident, is adorned with skulls, has her eyes half-closed by intoxication from drinking the blood of demons, and wears an elephant hide. She is also praised, however, as the daughter of Himalaya, a clear identification with Parvati. It seems that in the process of Parvati's preparations for war. Kali appears as ParvatFs personified wrath, her alter ego, as it were.

The Vamana-purana calls Parvati Kali (the black one) because of f her dark complexion. Hearing Lord Shiva use this name, Parvati takes offence and undertakes austerities in order to rid herself of her dark complexion. After succeeding, she is renamed Gauri (the golden one). Her dark sheath, however, is transformed into the furious battle queen Kausiki, who subsequently creates Kalf in her fury. So again, although there is an intermediary goddess (Kausiki), Kali plays the role of Parvati's dark, negative, violent nature in embodied form.

Kali makes similar appearances in myths concerning both Sati and Sita. In the case of Sati, Kali appears when Sati's father, Daksa, infuriates his daughter by not inviting her and Lord Shiva to a great sacrificial rite. Sati rubs her nose in anger and Kali appears. Kali also appears in other texts when Sati, in her wrath over the same incident, gives birth to or transforms herself into ten goddesses, the Dasamahavidyas. The first goddess mentioned in this group is usually Kali. In the case of Sita, Kali appears as her fierce, terrible, bloodthirsty aspect when Rama, on his return to India after defeating Ravana, is confronted with such a terrible monster that he freezes in fear. Sita, transformed into Kali, handily defeats the demon.

In her association with Lord Shiva Kali's tendency to wildness and disorder persists. Although she is sometimes tamed or softened by him, at times she incites Lord Shiva himself to dangerous, destructive behavior. A South Indian tradition tells of a dance contest between the two. After defeating Sumbha and Nisumbha, Kali takes up residence in a forest with her retinue of fierce companions and terrorizes the surrounding area. A devotee of Lord Shiva in that area becomes distracted from doing austerities and petitions Lord Shiva to rid the forest of the violent goddess. When Lord Shiva appears. Kali threatens him, claiming the area as her own. Lord Shiva challenges her to a dance contest and defeats her when she is unable (or unwilling) to match his energetic tandava dance.

Although this tradition says that Lord Shiva defeated and forced Kali to control her disruptive habits, we find few images and myths depicting her becalmed and docile. Instead, we find references or images that show Lord Shiva and Kali in situations where either or both behave in disruptive ways, inciting each other, or in which Kali in her wild activity dominates an inactive or sometimes dead Lord Shiva.

In the first type of relationship the two appear dancing together in such a way that they threaten the world. Bhavabhuti's Malatimadhava describes the divine pair as they dance wildly near the goddess's temple. Their dance is so frenzied that it threatens to destroy the world. Parvati stands nearby, frightened. Here the scenario is not a dance contest but a mutually destructive dance in which the two deities incite each other. This is a common image in Bengali devotional hymns to Kali. Lord Shiva and Kali complement each other in their madness and destructive habits.

- Crazy is my Father, crazy my Mother,

- And I, their son, am crazy too!

- Shyama (the dark one, an epithet of Kali] is my Mother's name.

- My Father strikes His cheeks and makes a hollow sound:

- Ba-ba-boom! Ba-ba-boom!

- And my Mother, drunk and reeling, Falls across my Father's body!

- Shyama's streaming tresses hang in vast disorder;

- Bees are swarming numberless

- About her crimson Lotus Feet.

- Listen, as She dances, how Her anklets ring!

Iconographic representations of Kali and Lord Shiva nearly always show Kali as dominant. She is usually standing or dancing on Lord Shiva's prone body, and when the two are depicted in sexual intercourse, she is shown above him. Although Lord Shiva is said to have tamed Kali in the myth of the dance contest, it seems clear that she was never finally subdued by him and is most popularly represented as a being who is uncontrollable and more apt to provoke Lord Shiva to dangerous activity than to be controlled by him.

In general, then, we may say that Kali is a goddess who threatens stability and order. Although she may be said to serve order in her role as slayer of demons, more often than not she becomes so frenzied on the battlefield, usually becoming drunk on the blood of her victims, that she herself begins to destroy the world that she is supposed to protect. Thus even in the service of the gods, she is ultimately dangerous and tends to get out of control. In association with other goddesses, she appears to represent their embodied wrath and fury, a frightening, dangerous dimension of the divine feminine that is released when these goddesses become enraged or are summoned to take part in war and killing.

In relation to Lord Shiva, she appears to play the opposite role from that of Parvati. Parvati calms Lord Shiva, counterbalancing his antisocial or destructive / tendencies. It is she who brings Lord Shiva within the sphere of domesticity and who, with her soft glances, urges him to moderate the destructive aspects of his tandava dance Kali is Lord Shiva's "other" wife, as it were, provoking him and encouraging him in his mad, antisocial, often disruptive habits. It is never Kali who tames Lord Shiva but Lord Shiva who must becalm Kali. Her association with criminals reinforces her dangerous role visa-vis society. She is at home outside the moral order and seems to be unbounded by that order.

The later history & the significance of Kali

Given Kali's intimidating appearance and ghastly habits, it might seem that she would never occupy a central position in Hindu piety, yet she does. She is of central importance in Tantrism particularly left handed Tantrism, and in Bengali Sikta devotionalism. An underlying assumption in Tantric ideology is that reality is the result and expression of the symbiotic interaction of male and female, Lord Shiva and sakti, the quiescent and the dynamic, and other polar opposites that in interaction produce a creative tension. Consequently, goddesses in Tantrism play an important role and are affirmed to be as central to discerning the nature of reality as the male deities are. Although Lord Shiva is usually said to be the source of the Tantras, the source of wisdom and truth, and Parvatl, his spouse, to be the student to whom the scriptures are given, many of the Tantras emphasize the fact that it is sakti that pervades reality with her power, might, and vitality and that it is she (understood in personified form to be Pirvati, Kall, and other goddesses) who is immediately present to the adept and whose presence and being underlie his own being. For the Tantric adept it is her vitality that is sought through various techniques aimed at spiritual transformation; thus it is she who is affirmed as the dominant and primary reality.

Although Parvati is usually said to be the recipient of Lord Shiva's wisdom in the form of the Tantras, it is Kali who seems to dominate Tantric iconography, texts, and rituals, especially in left-handed Tantra. In many places Kali is praised as the greatest of all deities or the highest reality. In the Nirvana-tantra the gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Lord Shiva are said to arise from her like bubbles from the sea, endlessly arising and passing away, leaving their source unchanged. Compared to Kali, proclaims this text, Brahma, Vishnu, and Lord Shiva are like the amount of water in a cow's hoof print compared to the waters of the sea.

The Nigama-kalpataru and the Picchila-tantra declare that of all mantras Kali's is the greatest. The yogini-tantra, the Kamakhya-tantra, and the Niruttara-tantra all proclaim Kali the greatest of the vidyas (the manifestations of the Mahadevi, the "great goddess") or divinity itself; indeed, they declare her to be the essence or own form (svarupa) of the Mahadevi. The Kamada-tantra states unequivocally that she is attributeless, neither male nor female, sinless, the imperishable saccidananda (being, consciousness, and bliss), brahman itself. In the Mahanirvana-tantra, too. Kali is one of the most common epithets for the primordial sakti and in one passage Lord Shiva praises her as follows:

At the dissolution of things, it is Kala [Time] Who will devour all, and by reason of this He is called Mahakala [an epithet of Lord Shiva), and since Thou devourest Mahakala Himself, it is Thou who art the Supreme Primordial Kalika. Because Thou devourest Kala, Thou art Kali, the original form of all things, and because Thou art the Origin of and devourest all things Thou art called the Adya [primordial Kali. Resuming after Dissolution Thine own form, dark and formless, Thou alone remainest as One ineffable and inconceivable. Though having a form, yet art Thou formless; though Thyself without beginning, multiform by the power of Maya, Thou art the Beginning of all, Creatrix, Protectress, and Destructress that Thou art.

Why Kali, in preference to other goddesses, attained this preeminent position in Tantrism is not entirely clear. Given certain Tantric ideological and ritual presuppositions, however, the following logic seems possible. Tantrism generally is ritually oriented. By means of various rituals (exterior and interior, bodily and mental) the sadhaka (practitioner) seeks to gain moksa (release, salvation). A consistent theme in this endeavor is the uniting of opposites (male-female, microcosm-macrocosm, sacred-profane, Lord Shiva-sakti). In Tantrism there is an elaborate, subtle geography of the body that must be learned, controlled, and ultimately resolved in unity. By means of the body, both the physical and subtle bodies, the sadhaka may manipulate levels of reality and harness the dynamics of those levels to the attainment of his goal. The sadhaka, with the help of a guru, undertakes to gain his goal by conquest-by using his own body and knowledge of that body to bring the fractured world of name and form, the polarized world of male and female, sacred and profane, to wholeness and unity.

Sadhana (spiritual endeavor) takes a particularly dramatic form in left-handed {vamacara) Tantrism. In his attempt to realize the nature of the world as completely and thoroughly pervaded by the one sakti, the sadhaka (here called the "hero," vira) undertakes the ritual of the pancatattva, the "five (forbidden) things" (or truths). In a ritual context and under the supervision of his guru, the sadhaka partakes of wine, meat, fish, parched grain (perhaps a hallucinogenic drug of some kind), and illicit sexual intercourse. In this way he overcomes the distinction (or duality) of clean and unclean, sacred and profane, and breaks his bondage to a world that is artificially fragmented. He affirms in a radical way the underlying unity of the phenomenal world, the identity of sakti with the whole creation. Heroically, he triumphs over it, controls and masters it.

By affirming the essential worth of the forbidden, he causes the forbidden to lose its power to pollute, to degrade, to bind" The figure of Kali conveys death, destruction, fear, terror, the all consuming aspect of reality. As such she is also a "forbidden thing," or the forbidden par excellence, for she is death itself. The Tantric hero does not propitiate, fear, ignore, or avoid the forbidden. During the pancatattva ritual, the sadhaka boldly confronts Kali and thereby assimilates, overcomes, and transforms her into a vehicle of salvation. This is particularly clear in the Karpuradi-stotra, a short work in praise of Kali, which describes the pancatattva ritual as performed in the cremation ground (smasana-sadhana). Throughout this text Kali is described in familiar terms. She is black, has disheveled hair and blood trickling from her mouth, holds a sword and a severed head, wears a girdle of severed arms, sits on a corpse in the cremation ground, and is surrounded by skulls, bones, and female jackals. It is she, when confronted boldly in meditation, who gives the sadhaka great power and ultimately salvation. In Kali's favorite dwelling place, the cremation ground, the sadhaka meditates on every terrible aspect of the black goddess and thus achieves his goal.

He, O Mahakali who in the cremation-ground, naked, and with dishevelled hair, intently meditates upon Thee and recites Thy mantra, and with each recitation makes offering to Thee of a thousand Akanda flowers with seed, becomes without any effort a Lord of the earth. 0 Kali, whoever on Tuesday at midnight, having uttered Thy mantra, makes offering even but once with devotion to Thee of a hair of his Sakti [his female companion] in the cremation-ground, becomes a great poet, a Lord of the earth, and ever goes mounted upon an elephant.

The Karpuradi-stotra clearly makes Kali more than a terrible, ferocious slayer of demons who serves Durga or Lord Shiva on the battlefield. In fact, she is by and large dissociated from the battle context. She is the supreme mistress of the universe, she is identified with the five elements, and in union with Lord Shiva (who is identified as her spouse) she creates and destroys the worlds. Her appearance has also been modified, befitting her exalted position as ruler of the world and the object of meditation by which the sadhaka attains liberation. In addition to her terrible aspects (which are insisted upon), there are now hints of another, benign dimension. So, for example, she is no longer described as emaciated or ugly. In the Karpuradi-stotra she is young and beautiful, has a gently smiling face, and makes gestures with her two right hands that dispel fear and offer boons. These positive features are entirely apt, as Kali no longer is a mere shrew, the distillation of Durga's or Parvati's wrath, but is she through whom the hero achieves success, she who grants the boon of salvation, and she who, when boldly approached, frees the sadhaka from fear itself. She is here not only the symbol of death but the symbol of triumph over death.

Kali also attains a central position in late medieval Bengali devotional literature.In this devotion Kali's appearance and habits have not changed very much. She remains terrifying in appearance and fearsome in habit. She is eminently recognizable. Ramprasad Sen, one of her most ardent devotees, describes his beloved Kali in almost shocked tones:

- 0 Kali! Why dost Thou roam about nude?

- Art Thou not ashamed. Mother!

- Garb and ornaments Thou hast none; yet Thou

- pridest in being King's daughter.

- 0 Mother! Is it a virtue of Thy family that

- Thou placest thy feet on Thy Husband?

- Thou are nude; Thy Husband is nude;

- You both roam cremation grounds.

- 0 Mother! We are all ashamed of you;

- Do put on Thy garb.

- Thou hast cast away Thy necklace of jewels,

- Mother, and worn a garland of human heads.

- Prasada says, "Mother! Thy fierce beauty has

- frightened Thy nude Consort."

The approach of the devotee to Kali, however, is quite different in mood and temperament from the approach of the tantric sadhaka. The Tantric adept, seeking to view Kali in her most terrible aspect, is heroic in approach, cultivating an almost aggressive, fearless stance before her. The Tantric adept challenges Kali to unveil her most forbidding secrets. The devotee, in contrast, adopts the position of the helpless child when approaching Kali. Even though the child's mother may be fearsome, at times even hostile, the child has little choice but to return to her for protection, security, and warmth. This is just the attitude Ramprasad expresses when he writes: 'Though she beat it, the child clings to its mother, crying "Mother".

Why Kali is approached as mother and in what sense she is perceived to be a mother by her devotees are questions that do not have clear or easy answers. In almost every sense Kali is not portrayed as a mother in the Hindu tradition prior to her central role in Bengali devotion beginning in the eighteenth century. Except in some contexts when she is associated or identified with Parvati as Lord Shiva's consort, Kali is rarely pictured in motherly scenes in Hindu mythology or iconography. Even in Bengali devotion to her, her appearance and habits change very little. Indeed, Kali's appearance and habits strike one as conveying truths opposed to those conveyed by such archetypal mother goddesses as Prthivi, Annapurna, Jagaddhatri, Sataksi, and other Hindu goddesses associated with fertility, growth, abundance, and well-beings These goddesses appear as inexhaustible sources of nourishment and creativity. When depicted iconographically they are heavy hipped and heavy breasted. Kali, especially in her early history, is often depicted or described as emaciated, lean, and gaunt.

It is not her breasts or hips that attract attention. It is her mouth, her lolling tongue, and her bloody cleaver. These other goddesses, "mother goddesses" in the obvious sense, give life. Kali takes life, insatiably. She lives in the cremation ground, haunts the battlefield, sits upon a corpse, and adorns herself with pieces of corpses. If mother goddesses are described as ever fecund. Kali is described as ever hungry. Her lolling tongue, grotesquely long and oversized, her sunken stomach, emaciated appearance, and sharp fangs convey a presence that is the direct opposite of a fertile, protective mother goddess. If mother goddesses give life. Kali feeds on life. What they give, she takes away.

Although the attitude of the devotee to Kali is different from that of the Tantric hero, although their paths appear very different, the attitude and approach of the devotee who insists upon approaching Kali as his mother may reveal a logic similar to that of the Tantric hero's. The truths about reality that Kali conveys-namely, that life feeds on death, that death is inevitable for all beings, that time wears all things down, and so are just as apparent to the devotee as they are to the Tantric hero. The fearfulness of these truths, however, is mitigated, indeed is transformed into liberating wisdom, if these truths can be accepted. The Tantric hero seeks to appropriate these truths by confronting Kali, by seeking her in the cremation ground in the dead of night, and by heroically demonstrating courage equal to he" terrible presence.

The devotee, in contrast, appropriates the truths Kali reveals by adopting the attitude of a child, whose essential nature toward its mother is that of acceptance, no matter how awful, how indifferent, how fearsome she is. The devotee, then, by making the apparently unlikely assertion that Kali is his mother, enables himself to approach and appropriate the forbidding truths that Kali reveals; in appropriating these truths the devotee, like the Tantric adept, is liberated from the fear these truths impose on people who deny or ignore them. Through devotion to Kali the devotee becomes reconciled to death and achieves an acceptance of the way things are, an equilibrium that remains unperturbed in Kali's presence. These themes are expressed well in this song of Ramprasad's:

- 0 Mother! Thou has great dissolution in Thy hand;

- Lord Shiva lies at Thy feet, absorbed in bliss.

- Thou laughest aloud (striking terror); streams of blood flow from Thy limbs.

- 0 Tara, doer of good, the good of all, grantor of safety,

- 0 Mother, grant me safety.

- 0 Mother Kali! take me in Thy arms; 0 Mother Kali! take me in Thy arms.

- 0 Mother! come now as Tara with a smiling face and clad in white; As dawn descends on dense darkness of the night.

- 0 Mother! terrific Kali! I have worshiped Thee alone so long.

- My worship is finished; now, 0 Mother, bring down Thy sword.

Ramprasad complains in many of his songs that Kali is indifferent to his well-being, that she makes him buffer and brings his worldly desires to naught and his worldly goods to ruin.

Mother who art the joy of Hara's [Lord Shiva's] heart, and who dost bring to naught the hopes of men, thou hast made void what hope was left to me. Though I place my soul an offering at thy feet, some calamity befalls. Though I think upon thy loveliness, unceasing death is mine. Thou dost frustrate my desires, thou art the spoiler of my fortunes. Well do I know thy mercy. Mother of mine. Great were my desires, and I spread them all out as a salesman does his wares. Thou didst see the display, I suppose, and didst bring confusion upon me. My wealth, my honour, kith and kin, all have gone, and I have nothing now to call my own. What further use is there for me? Wretched indeed am I. I have sought my own ends, and now there is no limit to my grief. Thou who dost take away sorrow, to me most wretched hast thou given sorrow. And I must all this unhappy lot endure.

He complains that she does not behave in the ways mothers are supposed to behave, that she does not hearken to his pleas.

- Can mercy be found in the heart of her who was born of the stone [a reference to her being the daughter of Himalaya?

- Were she not merciless, would she kick the breast of her lord?

- Men call you merciful, but there is no trace of mercy in you. Mother.

- You have cut off the headset the children of others, and these you wear as a garland around your neck.

- It matters not how much I call you "Mother, Mother." You hear me, but you will not listen"

To be Kali's child, Ramprasad often asserts, is to suffer, to be disappointed in terms of worldly desires and pleasures. Kali does not give what is normally expected. She does allow her devotee/child, however, to glimpse a vision of himself that is not circumscribed by physical and material limitations. As Ramprasad says succinctly: "He who has made Kali . . . his only goal easily forgets worldly pleasures". Indeed, that person has little choice, for Kali does not indulge her devotees in worldly pleasures. It is her very refusal to do so that enables her devotees to reflect on dimensions of themselves and of reality that go beyond bodily comfort and world security.

An analysis of the significance of Kali to the Hindu tradition reveals certain constants in her mythology and imagery. She is almost always associated with blood and death, and it is difficult to imagine two mere polluting realities in the context of the purity-minded culture of Hinduism. As such Kali is a very dangerous being. She vividly and dramatically thrusts upon the observer things that he or she would rather not think about. Within the civilized order of Hinduism, within the order of dharma, blood and death are acknowledged-it is impossible not to acknowledge their existence in human life-but they are acknowledged within the context of a highly ritualized, patterned, and complex social structure that takes great pains to handle them in "safe" ways, usually through rituals of purification.

These rituals (called samskaras, "refinements") allow individuals to pass in an orderly way through times when contact with blood and death are unavoidable. The order of dharma is not entirely naive and has incorporated into its refined version of human existence the recognition of these human inevitabilities.

But the Hindu samskaras are patterned on wishful thinking. Blood and death have a way of cropping up unexpectedly, accidentally, tragically, and dangerously. The periodic flow of menstrual blood or the death of an aged and loved old woman (whose husband has cooperatively died before her) are manageable within the normal order of human events. But the death of an infant or a hemorrhage, for instance, are a threat to the neat vision of the order of dharma." They can never be avoided with certainty, no matter how well protected one thinks one is.

Kali may be one way in which the Hindu tradition has sought to come to terms, at least in part, with the built-in shortcomings of its own refined view of the world. It is perhaps best and even redemptive to recognize that the system does not work in every case. Reflecting on the ways in which people must negate certain realities in their attempts to create social order, anthropologist Mary Douglas writes:

Whenever a strict pattern of purity is imposed on our lives it is either highly uncomfortable or it leads into contradiction if closely followed, or it leads to hypocrisy. That which is negated is not thereby removed. The rest of life, which does not tidily fit the accepted categories, is still there and demands attention. The body, as we have tried to show, provides a basic scheme for all symbolism. There is hardly any pollution which does not have some primary physiological reference. As life is in the body it cannot be rejected outright. And as life must be affirmed, the most complete philosophies . . . must find some ultimate way of affirming that which has been rejected.

Kali puts the order of dharma in perspective, perhaps puts it in its place, by reminding Hindus that certain aspects of reality are untamable, unpurifiable, unpredictable, and always a threat to society's feeble attempts to order what is essentially disorderly: life itself.

Kali's shocking appearance and unconventional behavior confront one with an alternative to normal society. To meditate on the dark goddess, or to devote oneself to her, is to step out of the everyday world of predictable dharmic order and enter a world of reversals, opposites, and contrasts and in doing so to wake up to new possibilities and new frames of reference. In her differentness, strangeness, indeed, in her perverseness, Kali is the kind of figure who is capable of shaking one's comforting and naive assumptions about the world. In doing this she allows a clearer perception of how things really are.

Kali allows (or perhaps forces) better perception by enabling one to see the complete picture. She allows one to see behind the bounteousness of the other goddesses who appear in benign forms. Kali reveals the insatiable hunger that logically must lie behind their amazing fecundity and liberality. Similarly, Kali permits individuals to see their overall roles in the cosmic drama. She invites a wider, more mature, more realistic reflection on where one has come from and where one is going. She allows the individual to see himself or herself as merely one being in an endless series of permutations arising from the ever-recurring cycles of life and death that constitute the inner rhythms of the divine mother.

As cycling and recycled energy, as both the creation and the food of the goddess, the individual is permitted to glimpse social roles and identities in perspective, to see them as often confining and as obscuring a clear perception of how things really are and who he or she really is. Kali reveals that ultimately all creatures are her children and also her food and that no social role or identity can remove the individual from this sacrificial give and take. While this truth may appear grim, its realization may be just what is needed to push one over the threshold into the liberating quest for release from bondage to samsara.

The extent to which Kali invites or provokes one over the threshold from order to antistructure is seen in the roles she requires of those who would establish any intimacy with her. Iconographically, it is Lord Shiva who participates in the most intimate relations with Kali. In probably her most famous pose, as Daksinakali, she stands or dances upon Lord Shiva's prone body in the cremation ground. His eyes are closed in bliss, sleep, trance, or death-it is difficult to say which. His attitude is utterly passive and, whether he is dead or not, his appearance corpselike. The myth that explains the origin of this pose says that once upon a time Kali began to dance out of control on the battlefield after having become drunk on the blood of her victims. To stop her rampage, Lord Shiva lay down on the battlefield like a corpse so that when she danced on his body she would stop, recognizing him as her husband. It is thus as a corpse, as one of her victims, that Lord Shiva calms Kali and elicits her graced.

In another myth it is the infant Lord Shiva who calms Kali and stops her rampage by eliciting motherly emotions from her. In this story Kali again has defeated her enemies on the battlefield and begun to dance out of control, drunk on the blood of those she has slain. To calm her and protect the stability of the world, Lord Shiva appears in the midst of the battlefield as an infant, crying out loudly. Seeing the child's distress. Kali stops her dancing, picks him up, and kisses him on the head. Then she suckles him at her breasts.

Both the dead and infants have a liminal nature. Neither has a complete social identity. Neither fits neatly or at all into the niches and structures of normal society. To approach Kali it is well to assume the identity of a corpse or an infant. Having no stake in the orderly structures of society, the devotee as corpse or infant is free to step out of society into the liminal environment of the goddess. The corpse is mere food for her insatiable fires, the infant mere energy, as yet raw and unrefined. Reduced to either extreme, one who approaches Kali in these roles is awakened to a perception of reality that is difficult to grasp within the confines of the order of dharma and a socialized ego.